Appellate Jurisdiction

By now yourselves will agree that the Act is a special Law and a self-contained code intended to address the increasing scourge of money laundering and provides for attachment of property derived from or involved in money laundering and prosecution of those involved directly or indirectly in the process or activities of money laundering.

In the Article titled ‘Consequences of Offence under Prevention of Money Laundering Act, 2002: The Draconian Mandate’, the Author did elucidate on the draconian provisions of the Prevention of Money Laundering Act, 2002 (‘Act’). Vide this Article, the Author has discussed the appellate remedies enshrined under the Act against such consequences.

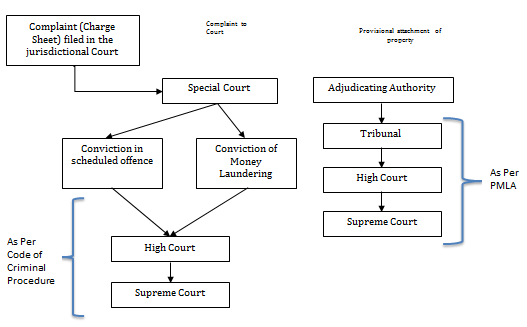

The Act provides for separate provisions pertaining to attachment and confiscation of property; and a separate procedure for adjudging an offence under the Act. Though, the Act provides for a well laid appellate remedy against the attachment of the property, it also lays down the aspect of a Special Court for the trial of the scheduled offence along with the offence under the Act. However, procedure regarding any appeal against the order of the Special Court is prescribed to be governed by the Criminal Procedure Code.

The procedure is explained via following pictorial representation.

With the backdrop of the above provisions, it is pertinent to note that the aggrieved party can proceed for appeal to the Tribunal, High Court and Supreme Court, only with respect to attachment or confiscation of tainted property, being proceeds from crime. The Act does not specifically prescribe for any recourse against the order of the Special Courts and refers to the provisions of the Code of Criminal Procure, 1973 for any appeal and revision of the order of the Special Court.

As highlighted in the earlier Article, the Act empowers the Director to attach and confiscate the tainted property suo-moto, for a maximum period of 180 days, provided that he has reasons to believe that the property has been acquired out of criminal proceeds of a scheduled offence.

Although, the very purpose of the provisions of provisional attachment is to curb concealment, transfer or dealing of the proceeds of crime to frustrate proceedings under the Act, appellate remedies are also provided under the Act to keep a check against such severe powers of the enforcement directorate.

As already discussed earlier, the Director or any other officer who provisionally attaches the property under the provisions of the proposed Act is mandatorily required to file a complaint before the adjudicating authority within a period of 30 days from such attachment. Going further, the Adjudicating authority shall serve a notice of minimum thirty days under section 8 of the Act, on the affected person requiring him to indicate the sources of his income, earnings or assets by which he has acquired such attached property and to show cause as to why such seized properties do not reflect criminal proceeds and hence shall not be confiscated by the Central Government. The Adjudicating Authority considering th reply of the person aggrieved, the Director, any other officer, and taking into consideration all the relevant materials, documentation and evidences placed on record, shall decide whether the property is involved in money laundering or not.

On affirmation by the Adjudication Authority, the property shall be attached and the possession of the same shall be taken over by the Enforcement Directorate, till the conclusion of the trial of an offence. However, if the Adjudicating Authority decides otherwise, the attachment order shall be revoked, subject to decision of the Appellate Tribunal.

Section 26 of the Act allows the Director or any person aggrieved in respect of an order passed by the Adjudicating Authority to prefer an appeal before the Appellate Tribunal within a period of 45 days or otherwise from the receipt of such order of the Adjudicating Authority.

Since, my fellow colleague in his Article has already discussed in detail the appellate remedy before the Hon’ble Money Laundering Appellate Tribunal, I shall throw some light on the provisions pertaining to the remedy from the Hon’ble High Court and Supreme Court in this regard.

Appeal to High Court

Section 42 of the Act provides that an appeal can be made before the Hon’ble High Court by an aggrieved person, against any decision or order passed by the Appellate Tribunal pertaining to attachment of the property. Although, appeal should be filed within a period of sixty days of communication of such decision or order, the High Court may entertain an Appeal beyond a period of 60 days if it is satisfied that the Appellant was prevented by sufficient cause from filing the Appeal within the said period.

Director or the person whose property is attached, whosoever is aggrieved by the order of the Hon’ble Tribunal can appeal before the Hon’ble High Court against the order of the Tribunal. In such a scenario, the jurisdiction of the High Court shall depend on the area in which the aggrieved party ordinarily resides or carries on business or personally works for gain; and in a scenario where the Central Government is the aggrieved party, the High Court within the jurisdiction of which the respondent, or in a case where there are more than one respondent, any of the respondents, ordinarily resides or carries on business or personally works for gain.

In view of the scheme of the Act, the Appeal to the Hon’ble High Court is the Second Appeal, the first being to the Appellate Tribunal against the order passed by the Adjudicating Authority.

Although, the Second Appeal, unlike many other statues is not restricted in its scope to the “Question of Law” but extends to the “Question of fact” as well[1], however, it is also an established fact that while determining whether the Question of Law arising in a case is a substantial one, the general rule is that the High Court will not interfere with the concurrent findings of the Courts[2] below unless the order appealed is not based on any evidence, or on misreading of evidence, wrong inferences, ignored evidences and facts etc.

Thus, in an appeal against the judgment of the Hon’ble Tribunal, Prevention of Money Laundering, the High Court, generally, is not required to go into the question of fact or appreciation of evidence, however, if it is apparent that certain evidences, information etc. was not considered or misconstrued etc., Hon’ble High Court may apart from ‘question of law’ can also consider the ‘question of fact’.

Writ Jurisdiction

Albeit, the Act lays down a formal procedure for appeal against the decision of the Adjudicating Authority pertaining to attachment of the property, being proceeds of crime, the Hon’ble High Court may entertain Writ petitions, even though an alternate remedy by way of normal forum of hierarchy of Tribunal and Courts is available.

However, Hon’ble High Courts shall entertain the Writ petitions and exercise their discretionary powers as provided in terms of Article 226 of the Constitution of India, only in exceptional circumstances, where either the Adjudicating Authority acted without jurisdiction or there was violation of the principles of Natural Justice. In the recent decision of the Hon’ble High Court of Delhi in the case of Rose Valley Hotels and Entertainments Limited v. Secretary, Department of Revenue, Ministry of Finance[3], while entertaining a writ petition filed against the confiscation order passed by the Adjudicating Authority, relied on the decision of the Hon’ble Supreme Court in the case of Whirlpool Corpn. v. Registrar of Trade Marks[4] , wherein, the Supreme Court laid down the triple test for entertaining a writ petition despite availability of the remedy of an appeal in contractual matters i.e., firstly if the action of the respondent is illegal and without jurisdiction, secondly if the principles of natural justice have been violated and thirdly if the petitioner’s fundamental rights have been violated.

In the case of Barik Biswas vs Union of India & Ors., Hon’ble High Court of Delhi also dismissed the writ petition and held that “the action of coming to this Court is premature and therefore, this Court is of the view that since the petitioners have effective and efficacious remedy under PMLA, necessitating institution of the petition by invoking extraordinary jurisdiction of this Court is not appropriate at this stage. If this Court were to enter into the merits of this case at this stage, it would amount to scuttling the statutorily engrafted mechanism i.e. PMLA.”

However, the Hon’ble High Court of Madras in the case of A.Kamarunnisa Ghori and Others[5], accepted the Writ Petition on a limited point, where the Enforcement Directorate and Adjudicating Authority interpreted the law in a way different from the view point of the Hon’ble Court. Against the argument of presence of alternate remedy, the Hon’ble Court held that “in view of the fact that the order of the Appellate Tribunal is ultimately subject to an appeal to this Court under Section 42 of the Act. By the time the petitioners go before the Appellate Authority and thereafter come up before this Court under Section 42, the petitioners would have long lost possession of their properties” and hence prejudiced.

The recent judicial pronouncements, highlight that although, the Hon’ble High Courts are not accepting the Writ Petitions pertaining to attachment of properties, since an alternate remedy is available under the law, however, if the authorities act in an preconceived, arbitrary manner without giving due regard to the evidences on record and the principles of natural justice, Hon’ble Court may act upon its discretionary power under Article 226 of the Act. The decision of the Hon’ble High Court shall also depend upon the type of the writ application, being Habeas Corpus, Mandamus, Certiorari, Prohibition and Quo-Warranto.

Special Courts

Scheme of the Act, provides power to a Special Court for trial of offence of Money Laundering as provided in Section 3 read with Section 4 of the Act. Special Court is nothing but Courts of Session which are designated as a Special Court for the purposes of such Act by the Central Government in consultation with the Chief Justice of High Court.

By virtue of Section 44 of the Act, the Special Court is entitled to try the offences under Section 3 read with Section 4 of the Prevention of Money Laundering Act as well as the connected scheduled offences. Thus, the Special Court shall undertake the trial of the Scheduled Offence along with the offence under the Act.

Shorn of all embellishment, the special Court is a court of original criminal jurisdiction and to make it functionally oriented some powers are conferred by the statute. It has to function as a court of original Criminal jurisdiction not being bound by the terminological status description of magistrates or a Court of Sessions except those specifically conferred and specifically denied. Under the Code, it will enjoy all powers which a Court of original criminal jurisdiction enjoys save and except the ones specifically denied.[6] The Court has to be treated as a Court of original criminal jurisdiction and shall have all the powers as any Court of original criminal jurisdiction has under the Criminal Procedure Code except those specifically denied. This clause provides that the offences punishable under this Act shall be tried only by the Special Court.

The Special Judge empowered under this Act, can try offences under the Prevention of Money Laundering Act along with Scheduled Offences. The said power of the Special Court to try an offence under the PMLA along with the scheduled offence was upheld by Jharkhand High Court in one of the matter[7] while discussing the provisions of Section 44 of the Act.

The Court which has taken cognizance of the scheduled offence, being a Court other than the Special Court which has taken cognizance of the complaint of the offence of money laundering, is enabled on an application by the authority to commit the case related to the scheduled offence to the Special Court. Upon the receipt of the case, the Special Court is mandatorily required to proceed to deal with the case from the stage at which it was committed.

Furthermore, the provisions of Section 47 of the Act provide for the appellate and revisionary remedy. In terms of the provision of Section 47 of the Act, the aggrieved party can avail the remedy of appeal to the High Court and the Supreme Court respectively against the orders of the Special Court, in terms of the powers and procedure laid down by Chapter XXIX or Chapter XXX of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973.

Thus, instead of providing a specific procedure, as laid down for the attachment orders passed by the Adjudicating Authority, the Act provides for the procedure laid down under the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 for appeal against the order of the Special Court.

Conclusion

Although, the Act provides for the concept of Special Courts for the trial of the offences alleged under any of the Scheduled Offences as well as the offences under the Prevention of Money Laundering Act, 2002, to speed up the trial and disposal of the abundant cases pending in multiple forums. However, in a country, where several matters are pending before different judicial forums for number of years, a parallel set of litigation, pertaining to the attachment and taking possession of the property, the fate of which depends entirely upon the decision of the Special Court, seems wastage of the precious time of the courts.

[1] Under the scheme of the Income Tax Act, 1961 first appeal is before the Hon’ble Commissioner of Income Tax(Appeals) and Second appeal is before the Hon’ble Income Tax Appellate Tribunal. Appeal before the Appellate Tribunal, being the second appeal is on the question of law as well as facts.

[2] Radha Mohan Lakhotia v. Deputy Director, Prevention of Money Laundering (Amendment) Act, 2010 (5) Bom.CR. 625

[3] [2015] 60 taxmann.com 427 (Delhi)/[2015] 131 SCL 749 (Delhi)

[4] [1998] 8 SCC 1

[5] WP No. 1912, 2870,13421 and 22062 of 2011

[6] A. R. Antulay v. R.S. Nayak & Anr. (1984) 2 SCC 500

[7] Hari Narayan Rai v. State of Jharkhand- 2010 Lawsuit (Jharkhand) 448 dt. 05.04.2010